Wednesday marked my first day back in the classroom since June 2012. I was nervous. Did I still know how to do this? Well, I might…but I couldn’t stand the thought of just doing what I had always done. Not so long ago, the topic of discussion for Global Math Department was the First Day of School. Reading about all the different ideas, I resolved not to spend my first 100-minute class period just going over rules and dress code. So after some reading about whiteboarding in class and researching some different problems, I chose the “When Should She Take Her Medicine?” problem from Robert Kaplinksy.

Over 10+ years of working with gifted and high-achieving 6th graders, I’ve noticed that they really struggle with patience when they get to me. They can’t wait to have the right answer…and they’re used to getting that answer FAST because they’ve almost never been asked to look past the immediate and obvious computation-based “problem.” That’s why the medicine problem seemed perfect for the first day.

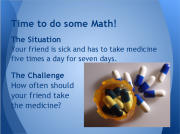

To introduce this activity, I created a slide to display the problem.  When I displayed the “situation,” their hands shot up immediately because they were sure the answer was 35. I apologized for misleading them to think that I’d be asking them to give answers to any obvious questions this year. Then I showed the “problem.” Of course, they thought they had an immediate answer for that, too. Then I walked them through the estimation process (high, low, best) and asked about assumptions being made (I had to define that term since they kept trying to tell me that they were assuming the answer was 4.5 hours). As soon as we covered the waking and sleeping times, the hands shot up again and giant 3s were being written on the boards. I asked them to convince me that their answer worked…show me with a timeline, schedule, list, something to prove they had a good answer. That’s when they started to unravel. They tried to show me that doses at 7a, 10a, 1p, 4p, and 7p worked, but then I’d ask them about the assumptions we made about the dose schedule. I asked if everyone in the group was 100% behind their answer and every time there was the one kid that said they weren’t sure it was a good solution for the person to be awake for 3 hours without getting any medicine. Then I encouraged the group to come up with a better solution that would address their teammate’s concern. (My favorite student work-around for this was shifting the doses up 1.5 hours to break up the three hour gap.)

When I displayed the “situation,” their hands shot up immediately because they were sure the answer was 35. I apologized for misleading them to think that I’d be asking them to give answers to any obvious questions this year. Then I showed the “problem.” Of course, they thought they had an immediate answer for that, too. Then I walked them through the estimation process (high, low, best) and asked about assumptions being made (I had to define that term since they kept trying to tell me that they were assuming the answer was 4.5 hours). As soon as we covered the waking and sleeping times, the hands shot up again and giant 3s were being written on the boards. I asked them to convince me that their answer worked…show me with a timeline, schedule, list, something to prove they had a good answer. That’s when they started to unravel. They tried to show me that doses at 7a, 10a, 1p, 4p, and 7p worked, but then I’d ask them about the assumptions we made about the dose schedule. I asked if everyone in the group was 100% behind their answer and every time there was the one kid that said they weren’t sure it was a good solution for the person to be awake for 3 hours without getting any medicine. Then I encouraged the group to come up with a better solution that would address their teammate’s concern. (My favorite student work-around for this was shifting the doses up 1.5 hours to break up the three hour gap.)

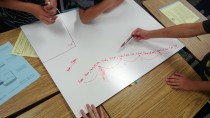

Here are some photos from the group that fascinated me.

1) This was the group that was the first to arrive at the answer of 3 hours (and most insistent their answer was correct.) I told them I wasn’t convinced and suggested that they find a way to convince me.

2) This is when I asked them to explain their dose schedule and how they arrived at this solution (every 3 hours). It didn’t take them too long to figure out that they actually had 6 doses, not 5. (If they had only seen that they had 5 intervals!)

2) This is when I asked them to explain their dose schedule and how they arrived at this solution (every 3 hours). It didn’t take them too long to figure out that they actually had 6 doses, not 5. (If they had only seen that they had 5 intervals!)

3) Making progress. Notice the repeated addition…they knew they needed to extend the interval, but unfortunately they were trying to add 2 minutes, 10 minutes, 15 minutes, etc. I found it interesting that no group tried converting the times to minutes to use a division algorithm.

The hardest part of the day was not helping too much. These kids worked on this problem in earnest for almost an hour and still didn’t get to a “best” answer. At times I felt like a member of the “Who’s Line is it Anyways” cast playing the questions game; the students asked questions and instead of giving them answers I just asked more questions. There were some huffs and sighs, some frustrated grunts, but they kept working. They kept going back to the problem. The different solution strategies were encouraging. It was good to see that they had some solid understanding of how to approach the problem, at least once they resigned themselves to the idea of not having an instantaneous answer.

One thing is certain; this problem threw these kids for a loop. I don’t think they knew whether to love it or hate it. I heard from one parent who works at the school that her daughter was talking about the problem all afternoon, telling them all about the problem, how I presented it, and how her group tried to solve it. I think I’m going to like this class. And it’s good to be back.

Pingback: Day Two | Rocking the Boat

Pingback: I Speak Math

We must teach the same 6th grade students! What really throws them is that I am not looking for the one “right” answer, but for the many different ways students solved the problem. Nice job with this medicine problem!

Thanks, Julie! I agree, my students are never sure what to think about me allowing them to solve problems in multiple ways. They’re so used to being told that there’s only one “right” way to work a problem. As I work with teachers to help them transition to CCSS, part of my work will be trying to convince them to eliminate the “my way or the highway” kind of thinking and teaching.

This is wonderful to read. I completely agree that “the hardest part of the day [is] not helping too much.” Fantastic job of letting them struggle. I hope you don’t mind me linking my lesson to this page to see how students experienced the problem.

Thank you, Robert. I don’t mind a link…I’m actually pretty flattered that you would even consider it. I’m looking forward to using a few more of your problems with this group. Thanks for sharing your work with us!