This post has been sitting in my draft folder for over a month. I originally stalled in finishing it because I wasn’t happy with my writing. I’m working to stop letting “perfect get in the way of good,” and so I’m posting this to get back into blogging. -Kate

One of the reasons I asked to teach a class this year (in addition to my duties at the district office) was to be able to try out a bunch of different strategies with students. I don’t want to be the leader that tells teachers they need to be using a strategy that I’ve only read about. Today I took a cue from Dave Burgess, the author of Teach Like a Pirate, by using what Dave refers to as a Taboo Hook. Dave writes that he has found making content seem taboo, secret, or otherwise off-limits makes students eager to hear it. I adapted this for my class to be the Too Advanced For You Hook.

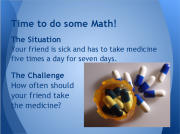

Today (9/4) was our first day of textbook-based lessons. They’re not my favorites, but for some topics they’re efficient. We covered powers and exponents, squares, and order of operations today. (100-minute periods….tons of time for that much review content.) Generally, my students don’t need review lessons. But they do need a chance to develop note-taking skills with less demanding content. To keep them engaged and challenged, I like to extend lessons to more advanced content, especially when a true conceptual understanding of the 6th grade content naturally leads to understanding of higher level concepts. Enter exponents and the Too Advanced For You Hook.

After quickly covering the vocabulary and meaning of exponents, then working through a few exercises with students, I paused for a few seconds and looked at the clock. I looked back and forth across the classroom and then said, “I don’t know. I don’t want to overwhelm you guys.” And that’s all it took. I had 10 kids instantly insist that I couldn’t overwhelm them. They didn’t know what I was going to give them, but they were already convinced that they wanted to get it. So, with just a little bit of planning and some good theatrical timing, I had 33 students practically begging to be taught about negative integers. During the last 20 minutes of the last period of the day. And they loved it.